Over the last few weeks Mike Anthony and our team at engage have been working with a client to draw insights from the huge bank of market research data they have amassed in the Asia Pacific region. Our purpose is simple: to identify key strategic growth drivers. As we come into the final weeks of our work on this, I’m surprised at how much data we’ve worked through and how little of it is actually applicable to the task at hand.

Over the last few weeks Mike Anthony and our team at engage have been working with a client to draw insights from the huge bank of market research data they have amassed in the Asia Pacific region. Our purpose is simple: to identify key strategic growth drivers. As we come into the final weeks of our work on this, I’m surprised at how much data we’ve worked through and how little of it is actually applicable to the task at hand.

Perhaps it’s time I questioned why my threshold of surprise is so low! After all, I’ve been doing work like this for nearly 15 years and no matter where I go around the world and what sort of company I work with, I always find the same thing – most research data is useless when it comes to supporting strategic decisions.

What’s wrong with market research?

The truthful answer is nothing, when it’s actually research. However, most of the ‘market research’ companies buy is not research at all, rather they buy narrative data. Narrative data tells stories: It allows us to see what has happened in the market, it helps us understand who has done what and sometimes it even helps us learn why things have happened. Note that these stories are always in the past tense – even ‘real time’ data tells us what has just happened. And, like the stories I read to my kids at night, some are interesting, some not so much and only a very few offer real insight into the nature of the world we live in.

The main reason why companies are awash with narrative data is because it’s cheap (relatively speaking) and because it enables consistent measurement. Think for instance about the Nielsen Retail Audit data. Nielsen have become world leaders in manufacturing narrative data by developing a highly systemized, internationally duplicable data gathering and management model that regularly produces relatively accurate market reports. These reports are delivered at a fraction of the cost that an individual manufacturer might incur to get the same data.

The global consistency of retail audit data has made it the de facto measuring tool for market share, and so everyone with a research budget feels like they ought to buy this data first. As budgets grow, companies add products like Kantar’s World Panel data and Millward Brown’s brand tracking data to the mix. And today those with deeper pockets are adding transaction data like that which Tesco offers under the Dunnhumby brand – all of which when aggregated together form an amorphous mass of “Big Narrative Dataâ€.

Is it all narrative?

Taken together most of our clients’ ‘market research’ budget is spent on this kind of narrative data. Once all these products have been purchased, what’s left in the budget is spent on either ad hoc studies conducted to test product or advertising concepts or on larger usage and attitude (U&A) surveys that are run periodically. Yet again the methodologies used to conduct these surveys just seem to add to the pile of narrative data.

Take for example U&A studies. Most seek to understand how a target market is using a group of products. A sample is selected randomly and a standardized set of questions is posed to deliver a relatively standardized output which describes how the sample behaves. The result? A description of behavior and a description of attitude. Narrative data!

What’s wrong with narrative data?

Narrative data is useful but only under certain circumstances – it’s brilliant when used to measure progress against KPIs. The trouble is narrative data are lousy at helping managers decide what the KPIs should be.

This is because it’s extremely difficult to identify business growth drivers that KPIs measure using sources like Retail Audit or World Panel. Sure, they can point to the general area where there may be opportunities – for instance a lag in market share or a shortfall in penetration. But because of the mass-production methodologies applied in gathering the data, they simply can’t provide enough detail to define why these gaps might arise.

The return of the scientific method

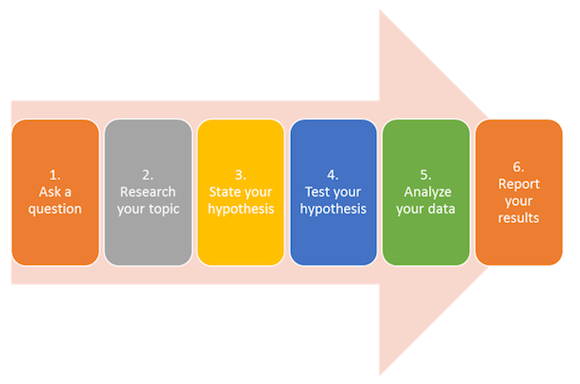

When defining what’s going to grow your business, a completely different process for research is needed. Most of us already know how to do this – we were taught it at school – it’s called the scientific method. The scientific method is pretty easy to get your head around and it consists of some very simple steps – so easy in fact that my seven year-old showed me something similar to this on the internet:

Narrative data helps form hypotheses, it’s the stuff you use in step two of the process. For example if your question is, “how will I grow my brand?†narrative data will give you clues as to where to look. Using those clues and what you already believe to be true, you can develop hypotheses. Real research is what’s done to test these hypotheses, and its value is that if your hypotheses are proven you can create concrete strategies for growth.

Narrative data helps form hypotheses, it’s the stuff you use in step two of the process. For example if your question is, “how will I grow my brand?†narrative data will give you clues as to where to look. Using those clues and what you already believe to be true, you can develop hypotheses. Real research is what’s done to test these hypotheses, and its value is that if your hypotheses are proven you can create concrete strategies for growth.

So many of us have forgotten this simple precept and as a result we are drowning in narrative data. In order to help, we’ve written a short eBook called The Introductory Guide to GREAT Shopper Research that gives a step-by-step guide to applying the scientific method to learning about shoppers.

Share this post: