I’ve just spent a long weekend in the UK. Not a big thing if you live in the US or Europe but a big stretch if you live in Asia! In advance of my trip my wife and I decided to take advantage of lower delivery fees to stock up on a few items that seem to cost twice as much in Singapore than elsewhere. After an hour of frenetic shopping we’d bought shoes and sports gear for the kids, tea bags and dishwasher tablets for friends in Thailand and (naturally) a horse riding helmet. In all we hit 6 websites including Amazon, Sainsbury, Boots, Sports Direct and two or three lesser known traders.

Upon my arrival on Saturday my mom expressed her amazement that so much stuff was waiting for me and indeed that a “very nice man” from Sainsbury had turned up to deliver tea bags. “Why,” she asked, “didn’t you get me to buy all this?” My mother’s bemusement at my behavior and the debate it provoked helps to illustrate how we have totally different needs as shoppers and what this might mean for the future of online and offline retail.

An online shopper’s needs

Let’s start with me. I guess that I’m a fairly typical online shopper – connected and brand aware but time poor. When I’m shopping, I’m looking to buy quickly and easily without compromising limited personal time. Like most shoppers I’m also anxious to ensure I get value from the stores I use.

Buying online suits me. I can shop at a pace that suits me, I don’t have to complete a purchase in one time segment; as long as I can meet a desired delivery slot, I can add to my order or change the products I buy when I choose. I can use ‘dead time’ to shop; adding to my shopping list when I’m stuck in traffic or between meetings. I don’t have to be ‘somewhere’ to buy because I can use my smartphone. And, I’m happy to exchange the time it would take to shop in the real world for the extra dollars I might pay for delivery services.

In all online shopping works for me because it meets my needs as a shopper.

An offline shopper’s needs

Now let’s think about my mom. She’s also connected and brand aware. Sure she belongs to a different generation, lives in a different environment and so on but if you look at many of the consumer brands we use, we have very similar preferences.

Where we differ hugely is in the way we shop. For my mother, shopping is a more leisurely activity. It’s an opportunity to leave the home and engage with other people. She’s happy to exchange her time for service and interaction. She enjoys exploring stores and her store choice reflects her preference for a pleasant shopping environment. As she ages, she believes that all these aspects of shopping will be become more important to her, not less.

Visiting real stores works better for her because they meet her needs as a shopper.

Different shoppers, different needs

If we were to look at a few of the brands we both use you might be lead to believe that as consumers my mom and I are relatively similar. But as shoppers it’s crystal clear that we have very different needs. This serves to show that brands do not have one type of shopper, but many. These shoppers have different needs, which drive different behaviors. My mom and I shop in different spaces, value different things when we are shopping, so applying the same marketing techniques to encourage us to buy is unlikely to work.

Too much of what I read about shopper marketing ignores this fundamental truth and too little of the activity I see recognises the opportunities. Successful shopper marketing ought to segment shoppers in ways that describe not just the consumption needs they serve but also their shopping behaviors. Marketers should prioritize which shopper segments are most important to their brands and learn how to influence each group of shoppers effectively, whether they are in the real world or online.

For some this will mean a major re-think and many will find the idea of marketing to multiple segments a stretch. However, those brands which embrace the challenge are likely to retain loyal consumers long into the future.

If you want to learn more about how to rise to the challenge, you might consider reading “The Shopper Marketing Revolution,” which gives marketers a step-by-step guide to bringing shopper thinking into the way they work.

It’s been an interesting week in the UK retail market. Just as February retail figures showed food discounts were dragging value from the market; Morrison’s a major British supermarket chain announced record losses. In the same week, Phil Clarke, the boss of the now-ailing Tesco, declared that future success is as simple as “putting the customers back at the heart of your business”. But is it that simple? I wonder, has the financial model of big retailers taken them too far away from the shopper?

It’s been an interesting week in the UK retail market. Just as February retail figures showed food discounts were dragging value from the market; Morrison’s a major British supermarket chain announced record losses. In the same week, Phil Clarke, the boss of the now-ailing Tesco, declared that future success is as simple as “putting the customers back at the heart of your business”. But is it that simple? I wonder, has the financial model of big retailers taken them too far away from the shopper? For many this has become a powerful rationalisation for expenditure in-store, especially as media fragmentation and retail consolidation fuelled a boom in point-of-purchase advertising. Indeed POPAI – the industry’s leading association, continues to heavily promote the benefits of in-store displays by publishing studies claiming that in excess of 70% of purchase decisions are made in stores.

For many this has become a powerful rationalisation for expenditure in-store, especially as media fragmentation and retail consolidation fuelled a boom in point-of-purchase advertising. Indeed POPAI – the industry’s leading association, continues to heavily promote the benefits of in-store displays by publishing studies claiming that in excess of 70% of purchase decisions are made in stores. Following my

Following my  Over the last few weeks

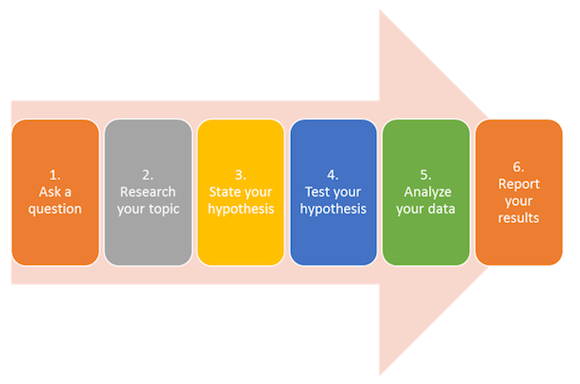

Over the last few weeks  Narrative data helps form hypotheses, it’s the stuff you use in step two of the process. For example if your question is, “how will I grow my brand?†narrative data will give you clues as to where to look. Using those clues and what you already believe to be true, you can develop hypotheses. Real research is what’s done to test these hypotheses, and its value is that if your hypotheses are proven you can create concrete strategies for growth.

Narrative data helps form hypotheses, it’s the stuff you use in step two of the process. For example if your question is, “how will I grow my brand?†narrative data will give you clues as to where to look. Using those clues and what you already believe to be true, you can develop hypotheses. Real research is what’s done to test these hypotheses, and its value is that if your hypotheses are proven you can create concrete strategies for growth.